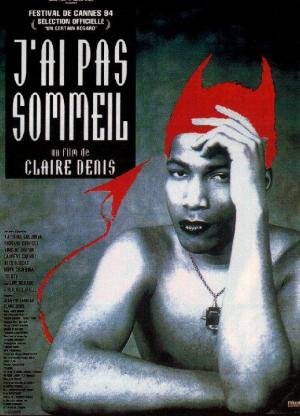

Perhaps just another serial killer movie from the 90s. But why does it not follow the similar beats narratively? This one feels like an odd one in Denis' filmography. To a certain extent the narrative thrust (as much as there is one here) is very of it's time - in the sense that the 90s were filled with schlocky (and sometimes not-so schlock) serial killer movies. But as one probably anticipates, this was not Denis' bid for mainstream accessibility, nor an exploration into the darkness of her soul (aka, The House That Jack Built). Perhaps it's due to the presence of Yekaterina Golubeva here that I am reminded of the work of her ex-husband, Šarūnas Bartas (who has a cameo in here).

The wider swath of characters and the focus on the more mundane and ordinary moments of life are more in common with the almost ethnographic "ambient narratives" of Bartas' work from this period. Though to be clear, there is more happening here than in his work. It's also interesting how Denis subverts stereotypes or cliches one might expect from certain characters early in the film, immediately setting this apart from films with similar plots. An immigrant from Lithuania, an interracial couple, and a gay drag-performer are all foreign. To the eyes of an audience, these are the people for whom must live difficult lives, and they are portrayed as such when they are featured as main performances in films (to this day), but here they exist. There is no daily crisis that obstructs their existence, no falsified movie event meant to deepen their struggle. Life happens, it goes on, with or without them. They are not pawns in a greater plan, they are people for whom we merely have a small window into their existence.

Their poverty is one of societal oppression and obstruction. Low to lower-middle class workers simply trying to live/achieve the dream of a middle-class life. These are people for whom thinking about a serial killer(s) on the loose in their city doesn't occupy a large space in their mind. A more pressing matter is simply trying to stay afloat - whether that means here (in Paris) or moving elsewhere.

Though formally this is a bit more locked off then I remember it being, this does appear to be the clearest distillation of Denis' formal approach to this point. A tonal core, isolated people from different backgrounds in a variety of personal/economic situations, links the strands together. But the iciness, the coldness of the perspective as a whole, binds the narrative together. Her perspective is never anything other than warm, but her gaze is unforgiving and unflinching. Everyone has a reason for what they're doing, whether it's taking a mediocre job or killing a random person, Denis does not let the viewer off the hook. You will acknowledge this person's existence. They live and breathe as you do, and there is no black and white, only gray.