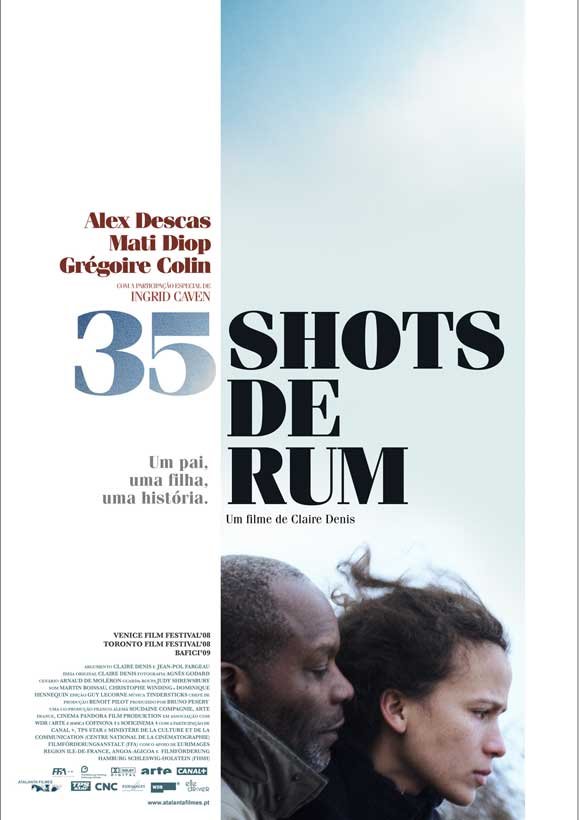

The moment when it hits, you'll know. When everything comes together into formation. A crystallization of form, content, and perspective into a hardened diamond of pure aesthetical poetry. Where narrative seems to dissolve into the ether of a piece. Character is reduced into bodies moving into, past, against one another. Shapes crisscrossing.

Not so much a work of montage (ala Mann's Ali) but a work of refinement of style. If Denis managed to hit upon her trademark, free-roaming camera gliding over bodies and landscapes with Anges Godard in her last film, Nénette and Boni, then here she finds their groove. The pocket in which their work becomes wholly singular to them and them alone. The masculine physical form rendered into poses akin to Roman and Greek statues. Posturing and posing before our eyes. Perhaps not since Leni Riefenstahl's Olympus films has the male form been so stunningly captured. Admiring but also distant, knowing the violence that stirs beneath these boy-ish facades.

A war film typically focuses on the events in said war. The violence created from man and machine - bullets being fired colliding with the flesh, bombs detonating, etc. etc. But very few focus on the actual conflicts - man against man (not in a strictly gendered way, to be clear). The violence of two bodies, two personalities clashing in the field. Thrown about in fury. What is the actual war? Such mundanities that occupy the life of a soldier and ultimately cause friction between them.

But these soldiers also occupy a space that does not rightfully belong to them. In theory, a soldier should be stationed out to protect whatever public from some sort of threat, but the only threat is from these very soldiers themselves. What is their purpose? To occupy the area. To fill a quota on a base. Safety for the public means frustration for those who have been hardened by the war(s) they have survived. One must challenge and demonstrate dominance over others as a form of perseverance in the face of boredom. Your right to exist isn't challenged (in this instance) but your right to land is.